Reviewing the evidence for vaccinating children against COVID 19

Highlighting recent research on the impacts of COVID-19 in children and adolescents.

This article was posted on Sheena Cruickshank’s substack last week.

A couple of years ago I wrote an article in The Conversation about the quiet removal of the offer to vaccinate primary age children to protect them against COVID-19 in England. The decision was that any child who turned five after August 2022 would not be eligible to receive a COVID vaccine until they are 12, unless they are in a higher-risk group. Vaccines for children under the age of 4 (from the age of 6 months), whilst approved for use on the UK, are not, nor have been, provided. This is very different to other countries including the USA which do offer vaccines to children from 6 months of age. What I want to do this with article is talk through some recent studies on paediatric infection and consider the potential implications of that, if any, on vaccine policy.

Why are most children not offered COVID-19 vaccines in the UK?

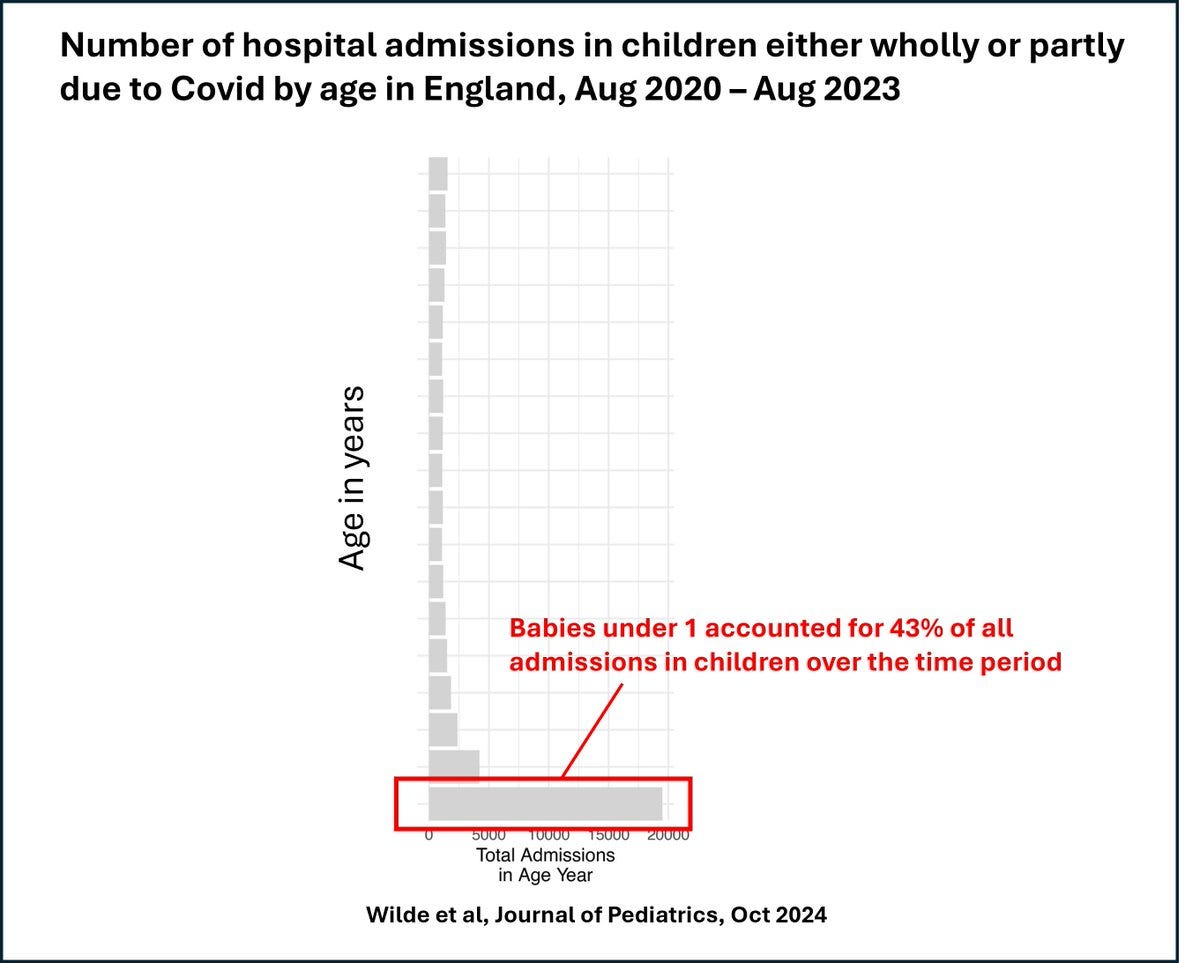

The reason for this is the idea that COVID is a less serious infection in young children than it is in adult. Whilst this can be true for many children, some do experience worse infections and a recent paper has looked at data in the UK regarding hospitalisations for COVID-19 across age groups. I also encourage you to read Christina Pagel’s excellent substack summarising the findings here.

The research analysis summarised in Professor Pagel’s substack showed that over 40% of all admissions in children between 2020 and 23 (under the age of 18) were in infants under the age of 1.

Vaccines and pregnancy.

Young infants are exceptionally vulnerable to COVID 19. The reason for this is that infants’ immune systems are still developing which makes them particularly vulnerable to any infection including COVID-19. The good news is that babies can be protected from COVID-19 in the first six months of life if the mum has been recently vaccinated. This is because if the mum is vaccinated she can pass on protective antibodies to the developing baby whilst pregnant. These will wane over time but if the mum is then able to breastfeed she can then top up the baby’s antibodies further by passing on antibodies that are found in breast milk.

Covid vaccines in pregnancy are recommended in the UK. These vaccines are recommended as the severity of COVID-19 is higher in unvaccinated than vaccinated women. Although the risk in the post-omicron era is lower, there is still a greater risk to the mum and baby from COVID-19. However, takeup of COVID-19 vaccines has not been great in pregnant women. For example, a study showed that only 1 in 3 pregnant women would have the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy. Younger women and people from socially economically deprived backgrounds were least likely to be vaccinated. Much more targeted work must be done to work with pregnant women and explain why these vaccines are both safe and important. Dr Viki Male maintains an excellent and up-to-date list of research on vaccines and COVID-19 in pregnancy so do look at her google document if you have further questions.

What are the risks of COVID-19 for older children?

Whilst I would personally advocate that infants and children would benefit from the offer of a vaccine between 6 months to 4 years of age to help develop their immunity so their first encounter with COVID-19 is helped and shaped by vaccine induced immunity, its unlikely the policy in the UK will change.

The current rationale influencing UK policy is that most children will be exposed to infection via school or nursery and that the risks of severe impacts of COVID are low. This is because most children with COVID-19 remain asymptomatic or develop mild disease, often with upper respiratory symptoms. The proportion of children over the age of 1 who get severe disease is still rare. Of those children that do get severe disease, it has been suggested that many children who require hospitalised with Covid have underlying health conditions. This thinking then influences the policy decisions. However, in older children (over the age of 1) this is true for around half of all hospitalisations though so that reasoning doesn’t quite chime. However, it is true that overall deaths from COVID in children DO remain rare which is very good news. The green book (which publishes data and recommendations for vaccines) cites a 2022 study which showed an infection fatality ratio of less than 1 in 100,000 infections in 0-19 year-olds. The risk is therefore considered low and decision makers have been concerned this risk is outweighed by the possible risk of acute resolving myocarditis from the vaccine in adolescent boys.

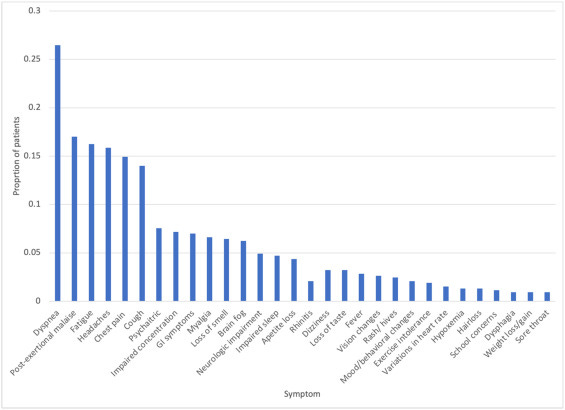

However, infection is NOT risk-free and some children do develop Long Covid (symptoms that last more than 4 weeks). We still do not understand why this happens and how we can better identify children who are most at risk. This is important so we can establish who falls into the more vulnerable groups that are currently eligible for vaccines. A recent scoping review was published investigating Long Covid in 659,286 children and adolescents under the age 21. A scoping review looks at the published literature and tries to build a consensus of what the research is telling us. The incidence of Long Covid was really variable in children so we need to better understand the true incidence- one study for example suggested 3.7% children developed Long Covid symptoms. Surprisingly, 80% of the cases of long Covid started with a mild infection. This suggests that severity might not be the best indicator of vaccine eligibility and must be followed up. Symptoms very hugely variable but many children described how this affected their day- to day lives a lot (see below). This must be absolutely devastating and we must understand why some children get Long Covid symptoms.

Many of the children identified in the scoping study had pre-existing conditions including a spectrum of allergic conditions (asthma, allergy, allergic rhinitis) and/or obesity. These are not necessarily all groups considered at risk and eligible for childhood vaccines in the UK. Of these criteria, only children with severe asthma that is poorly controlled are currently eligible. This scoping study needs following up but, as vaccination reduces the likelihood of developing post-Covid complications, it could suggest we may need to revise eligibility for the vaccines in children to further reduce the risk of Long Covid in children.

Other risks of infection should be evaluated. A recent paper showed the growing incidence of juvenile type II diabetes within 6 months of the diagnosis of COVID 19 in children between 10 and 19 years of age. Studies like this show the need to continue to assess the impacts of the infection in the un-vaccinated.

It is vital that we understand the scale of the risks, and who are most at risk so that if can ensure that decisions regarding vaccinating children are made in the light of all the most up to date evidence. Much more work is needed too to enhance vaccine information, address vaccine hesitancy and take-up in pregnant women so that babies can be best protected from COVID-19.